February 21, 2010 – Deutsche Welle Persian

Language reflects the culture of the people who speak it, represents their identity, and describes their world. Language is a phenomenon that, like a living being, exists with the people who speak it, helping them express and understand their world, and sometimes, it even dies. In short, language lives with its speakers. This is where the term "mother tongue" comes to mind—a term that may initially seem completely clear in its meaning and definition, but upon closer examination, it is not.

Mother tongue is sometimes defined as the first language a child learns. This definition, however, is subject to debate. Immigrant children and children born into ethnic or even religious minorities do not necessarily learn their mothers’ language, or they may not become as proficient in it as they are in the dominant language of their host country or ruling ethnic group. In other words, the mother tongue is not necessarily the most important language that remains in a person’s life or plays a role in it.

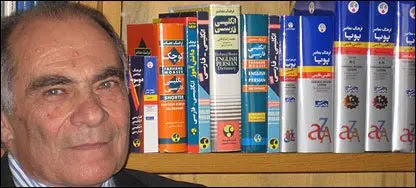

Dr. Mohammadreza Bateni, a renowned and veteran Iranian linguist, defines the mother tongue as follows:

"The mother tongue, as its name suggests, is the language a child first hears from their mother and learns. However, this term can be misleading because the mother tongue is not always the most important language in a child's life. For this reason, linguists today use the term ‘first language’ instead of ‘mother tongue.’ They say first language for what is learned first, second language for what is learned later, and so on.”

|

| Dr. Mohammadreza Bateni |

In Iran, various ethnic groups live with their distinct languages and cultures. While the right to learn the mother tongue of different ethnic groups in the country is ostensibly recognized, it lacks sufficient and effective governmental support.

Article 15 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic emphasizes that Persian is the official language and script of the country and that educational materials must be in this language. However, it also states:

"The use of local and ethnic languages in the press and mass media, as well as teaching their literature in schools alongside Persian, is allowed."

Although radio and television in many provinces broadcast programs in local languages, serious attention is not given to teaching these languages in schools.

The deprivation of education in their mother tongue presents many Iranian children with numerous challenges, especially in elementary school. Furthermore, as UNESCO experts have noted, oral languages face greater risks of extinction than written languages.

Linguistic Diversity and Mother Tongue

As noted, many consider the mother tongue to be the native language or the language of one’s parents. Supporting and providing opportunities to learn it—especially for immigrants and ethnic minorities—is regarded as a critical step in preserving linguistic diversity. Discussions about the mother tongue become particularly complex and fascinating when issues of ethnicity, identity, and bilingualism arise.

The term "bilingualism," like "mother tongue," appears straightforward at first glance but is more nuanced. Dr. Emilia Nercissians, a linguist and sociologist of education specializing in bilingualism, refers to the various types or degrees of bilingualism.

She states:

"We have individuals who are fully bilingual. This means they can completely and effectively use two languages in different or diverse contexts. However, being fully bilingual does not happen automatically. Social, political, and cultural conditions of the region where a person lives must also be conducive. We also have bilinguals who are not entirely balanced. This means one of their languages is dominant over the other, and the reasons for this need to be examined within the society.”

|

| Dr. Emilia Nercissians |

Dr. Nercissians highlights the case of Armenians in Iran:

"For Armenians, the Armenian language is the language of the home, the language a child uses to speak with their parents. Since Armenians are a relatively close-knit community, they also use Armenian in their interactions with friends or in Armenian schools. However, this Armenian language does not find opportunities for further growth, cultivation, or development. A language limited to the home consequently does not advance, as it lacks diverse contexts for practice. Their social spheres are also restricted and do not involve much interaction with larger groups, such as Persian speakers. Thus, they do not learn Persian as effectively either."

The Connection Between Mother Tongue and Identity

Mother tongue and identity share a close relationship. The question arises: Does one’s level of proficiency in a language affect which language they consider their mother tongue?

According to Dr. Mohammadreza Bateni, this question cannot be answered universally and must be addressed case by case. He explains:

"Someone may be Turk and have moved to Tehran at the age of 5. Another might move in search of work at the age of 35 or 40 and speak broken Persian. However, their sense of identity and pride in being Turk makes a difference. That child who moved at age 5 and now speaks Persian without an accent might still say, 'I am Turk' and participate in Azerbaijani associations in Tehran."

Dr. Nercissians agrees, adding:

"The issue of language ownership or forming an identity with a language can also have an individual aspect, where someone feels a stronger connection to Group A or Group B. Moreover, emotional bonds a person might have with these languages can also play a role."

The Growing Threat to Languages

The destruction of natural habitats and forced relocations of small tribes and ethnic groups to the outskirts of major cities or camps are significant threats to mother tongues.

In recent decades, many forest-dwelling tribes have lost their languages and ethnic identities in this way. Internal wars and large-scale migrations of defeated ethnic groups to neighboring countries have also contributed to the disappearance of some languages.

Modern times and the structural changes in traditional human life have limited the spaces for small groups, leading to the spread and dominance of a few major languages across most of the global population. Oral languages—estimated to number about 1,200—are particularly at risk of extinction. A significant portion of these languages belongs to the people of Africa, who speak around 2,000 languages.

According to UNESCO estimates, out of approximately 6,000 known languages in the world, over 3,000 are endangered. These languages are currently used by very small groups and have little chance of survival. Ninety-six percent of the world’s languages are spoken by only 4% of the global population. For example, in Papua New Guinea, located in the Pacific Ocean, there are over 800 languages, some spoken by fewer than 200 people. The total population of these islands is less than seven million.

UNESCO believes efforts must be made to ensure that lesser-known languages coexist with dominant languages. Considering the role of language in shaping individual identity and the cultural identity of ethnic groups and nations, such efforts could enrich global culture.

The link to the original article in Farsi on Deutsche Welle Persian:

زبان مادری و دوزبانگی